Despite going to bed relatively late after the night dive, our next day in Hawaii started very early. We didn’t realize it at the time, but it was to be the longest, most tiring day of our vacation.

Despite going to bed relatively late after the night dive, our next day in Hawaii started very early. We didn’t realize it at the time, but it was to be the longest, most tiring day of our vacation.

I wanted to spend some time in the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, but didn’t know what to expect. Would the park be crowded? Would it take more than one day to see it all? Would the active steam vents – as our guidebook said – lose their grandeur as the day warmed up?

We were staying in Kona and the points of interest were on the other side of the island, a three-hour drive away. We left at 5:30am, hoping to pull into the park early enough to see the steam while the air was still cool.

The drive from Kona to Kilauea was nice, if rather long. The traffic was sparse and the road alternated between long, straight stretches and Hana-like curves that slowed us to a crawl. We drove through arid, almost desert-like regions, soggy hillsides thick with vegetation, barren black lava fields along the jagged southern coastline, and finally into the rolling hills of the park.

We paid a $10 fee at the gate and drove straight to the visitor’s center. A park ranger had just opened the doors and was going about the business of posting the daily activity reports. We had a quick look around, asked a few questions, and drove off on a road called Crater Rim Drive, which encircles the mostly-dormant craters of Kilauea.

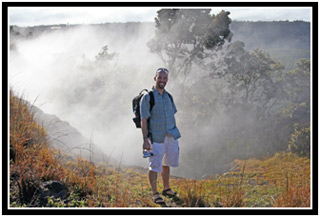

We skipped the first point-of-interest, Sulfur Rocks, for the steam vents that were just a quarter-mile down the road. There was only one other car in the parking lot – getting up early had paid off for us. I dug out our cameras as Oksana changed into warmer clothes; it was windy and the early morning mountain air was still cold.

Steam vented up out of the earth right next to the parking lot, but a more impressive view was revealed after a two-minute walk. Behind a metal railing rimming a truly massive crater, we stood amid the sulfury-steaming clouds billowing out over its edge.

This crater, its diameter measured in miles, was all flat and black; frozen lava. The sheer walls and level floor were devoid of any significant plant life. There was no telling how long ago molten rock had flowed across its surface, but it was not nearly enough time for the vegetation, even in Hawaii’s favorable climate, to begin the inevitable takeover.

Before Oksana and I visited the active volcano, Arenal, in Costa Rica, I anticipated seeing rivers of lava, explosions throwing magma into the air, and ponderous ash clouds. It was only after we saw the volcano that I learned all the videos we had seen on TV, all the postcards sold in the stores, and all photography books we had admired, had been shot decades before, during the latest explosion. Currently a visitor to Arenal can only expect to see steam spewing calmly out of the peak and the occasional cooling lava boulder tumbling down the dusty slopes.

Even though most of the television documentaries on Kilauea I had seen before coming to Hawaii insisted that it was the most active volcano on the planet, I tried not to get my hopes up. Unfortunately, when I looked out over that frozen crater, I realized that, once again, I was disappointed. I couldn’t help but imagine what it must have looked like – a lake of lava! – when it was being created. Is it wrong to wish for an eruption when you’re sitting on the top of a volcano?

Our next stop along Crater Rim Drive was the Jaggar Museum. As you would expect of a small on-site museum, it had a number of displays and videos that presented information about the area. There were stunning videos of previous lava eruptions, strange rock formations, and through a glass window, five or six seismographs busily drawing their squiggly little lines. Interesting stuff, to be sure, but it was the view outside that made stopping worthwhile.

We continued our drive. West of the crater, we parked our car next to a sign showcasing a rift zone. Due to some impressive past geologic activity, a large crack had split the earth open, spreading it apart. We decided to walk along the edge of it up to the crater wall. We didn’t stay long; there was the sulfurous smell of rotten eggs in the air. The information center had posted the day’s air quality readings as “safe” in all areas of the park, but a burning aftertaste had tenaciously taken up residence in our throats. We needed to get downwind, and in a hurry.

On the far side of the crater, almost directly across from the museum, was yet another turnout. Across a field of venting, steamy holes, a wooden observation platform had been erected on the edge of the wide crater-within-the-crater, called Halemaumau. Standing at the railing, we could see dozens, if not hundreds, of offerings left to Pele. Most consisted of flowers; some were rocks wrapped up in banana leaves.

More than half-way done with our drive around the park, we drove into a heavily forested section of the road. We made multiple stops, each time leaving the car for a short hike with our cameras. Each one was worth far more time than we gave it.

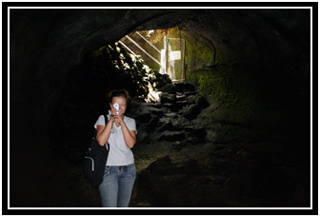

•The Thurston Lava Tube is a huge tunnel that has been carved out of earth by the progression of fast-moving lava. The first 100 meters or so were well lit and traveled, but beyond an unlocked gate you could explore an additional 300 meters. Unfortunately, we’d left our flashlights back in the car…

•The Kilauea Iki crater is a huge, steep bowl with an almost perfectly flat, black floor. From the observation platform we watched tiny people walk along a faint white line worn into the rock by untold numbers of tourists.

•The Trail of Destruction is a path built next to a whole mountainside that had been overtaken by some past lava flow. Stern signs warned against leaving the path. (The whole area was under observation to determine how life takes back such a barren landscape and a single errant seed – caught in a shoe, perhaps – could unnaturally affect the results.) Dead white trees and delicate new ferns shared the field of rock.

We arrived back at the park entrance just before noon. The visitor’s center was crawling with hundreds of tourists; Once again, I was happy to have beaten the crowd. We pulled in to regroup, check our maps, and make plans for the rest of the day. Activities had been posted, but my hope for a tour across the shoreline to see actual lava flows was nowhere to be seen. The only actively we were even remotely interested in, a tour of one of the craters along the Chain of Craters Trail, was fast approaching, but we were in desperate need of lunch.

We decided to drive out of the park and into a tiny town called, appropriately enough, Volcano. We drove past a restaurant, a café, and a general store before realizing that we had driven right out of town. We turned around and went back to the store and made sure to buy enough water for a hike later in the day. We stopped in at the café, but it was busy and, after a five minute wait without even being seated, we decided to skip lunch and finish off the snacks we had packed.

While sitting out in the parking lot, I decided to change tapes in the camcorder and dump our digital photos off to my laptop. Oksana passed the time flipping through one of the tour guide magazines that had been following us around. Glimpsing advertisement after advertisement for helicopter tours gave me an idea. I opened up my cell phone and decided to give one a call.

Blue Hawaiian Helicopters was picked at random and I asked them if they happened to have any tours for that afternoon. Serendipitously, they had just two seats left for their 3:30pm flight out of Hilo. I figured that the chances of us getting back to this side of the island for a heli-tour were slim (and the same tours were almost twice as expensive out of Kona), so after a quick consult with Oksana, we decided to reserve the seats.

We left Volcano for the Hilo and arrived a bit early for our flight. We checked in and passed the time in the open-air airport – I blogged; Oksana photographed flowers.

At around 3pm, we were ushered into a waiting room with two sprawling families. We watched a brief safety video and were outfitted with emergency life jackets. Finally, we were split up into groups of six and given our helicopter and pilot designations.

Out on the tarmac, we were loaded one at a time. All my bargaining with Oksana on who would receive the window seat became moot when I realized that we didn’t have the privilege of choosing; we were being seated by weight. Oksana got the window behind the pilot, I was stuck in the middle.

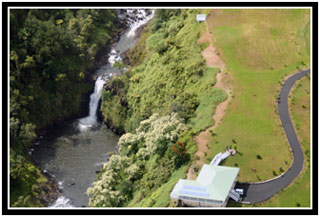

We donned our headphones and introduced ourselves to the pilot. As we lifted into the air, he began a well-rehearsed program. Music from the Superman soundtrack played as we gained altitude and he interrupted it every once in awhile to tell us what we were seeing outside the windows. I was interested in what he had to say about the waterfalls and volcanoes, I suppose, but I could have done without the minutia of Hilo homeownership.

The highlight of the flight was when we crossed over the portion of Kilauea, down near the southern shoreline of the Big Island, which was actually active. A brisk wind was blowing the steam out to sea and with multiple passes around the crater, we were able to look down into active vents or “skylights.” For the most part, we could only make out the bright orange of liquid rock – magma! – but on one of the last passes, both Oksana and I caught a glimpse of a splattering splash of lava. She even managed to capture it on tape.

Regrettably, the lava wasn’t being forced up and out of the small craters we were flying over, but rather it was flowing beneath the surface down towards the sea. Our low altitude was more than enough to give us a view of the huge cloud of dense steam rising up from the shoreline where the lava was making contact with the sea water. Before our eyes, Hawaii was growing.

Our pilot turned the helicopter toward the ocean and we passed over many miles of lava fields. Here and there among all that once-fiery rock were small green oases of life. Only a handful of microhabitats had been spared as the lava flowed around them.

Out by the sea, the wind was grabbing hold of the billowing steam cloud and pulling it along the shore. From our altitude we could see sheer cliffs that had been formed when immense shelves of lava had broken off and fallen into the sea. The blue of the pacific was marred by streaks of brown near the lava’s entry point as the sulfur dispersed into the water. Further west, at least a couple miles away, the end of the Trail of Craters Road literally dead ended where the lava flow had crossed its path. We could see dozens of cars parked at the terminus and tiny figures making their way out into the field of rock.

It was then that the kids in the helicopter tossed their groceries, one right after the other.

I couldn’t fault them for their airsickness, but it did put a damper on our flight back to Hilo. While Oksana and I wrinkled our noses, I couldn’t help but wonder why the pilot didn’t offer any words of condolences via our headsets. In fact, he barely motioned towards the lemon-scented handi-wipes before launching back into his flight monologue. When I remarked on this peculiar behavior afterwards, Oksana reminded me that the flight was being videotaped; not many tourists would appreciate a vomit-reminder in their vacation footage. (But hey, I just wrote it down so we’ll remember!)

Back on the tarmac, their mother tried to apologize to us over the roar of the helicopter blades. We knew from the introductions that her name was Nadia, and her noticeable accent confirmed our guesses. She was from Vladivostok and, as we walked back to the counter to get our stuff, Oksana chatted with her in Russian.

Once we’d picked up our bags, Oksana and I stepped back into the waiting area and asked about the videotapes of the flight. They were offering VHS tapes for $20 – I watched them reviewing the footage on a TV screen behind the counter. It wasn’t all that impressive, but after the price gouging for the manta video, $20 seemed reasonable. Just before laying out the cash for our copy, I noticed 3 Sony DVDirect recorders behind the counter. I inquired about the feasibility of buying a DVD instead, but they informed me that was a pilot project that they were testing on only one flight. I wish they would have mentioned that beforehand; the Digital Media Specialist in me would have requested a different helicopter.

It was about 4:30pm when we left Blue Hawaiian Helicopters and although I knew we’d pay for it later, I wanted to make the drive down to those shoreline lava fields we had seen during the flight. On our way out of Hilo, we made three quick stops: McDonald’s for dinner, Wal-Mart for socks (and an impulse-buy, $.85 flashlight), and Chevron for gas.

It took us an hour to get back to Volcano and another hour to drive almost straight down Trail of Craters Road. Sunset was fast approaching and though there were many enticing roadside attractions to explore, we only stopped the car twice. I worried that we wouldn’t get close enough to see the lava before dark.

When we finally reached the end of the last section of road, I knew we were in trouble. The dozens of cars we had seen from the helicopter had multiplied into hundreds. Surprisingly (to me, anyway) everyone had had the same idea – watch the steam billowing from the ocean at sunset, see the lava after dark. I didn’t mind the company, but they had taken all the parking places. One long line of unbroken cars, parallel parked on the inland side of the road, stretched back almost a mile.

We drove to the road’s end, by the ranger station and the restrooms, just on the off chance that someone might pull out in front of us. By the time we reached the tiny cul-de-sac, Oksana was ready to climb out of the car with all our gear. I drove back at least half a mile, probably further, before I found a place to park. I jumped out, donned a new pair of socks, and quickly exchanged my Tevas for my hiking shoes.

Three steps from the car, I realized that was probably a mistake. Although scabbed over, the holes in my heels were far from recovered, and I worried that by the end of the night I’d have blood filling up the back of my socks. But our guidebook had warned us repeatedly about all the stupid tourists who trekked out over the lava in their sandals… The sun was about to disappear behind the steep hillside we had just drove down; I wanted to run to catch up to Oksana, but I concentrated on a fast walk instead. Each step was acutely painful, but after awhile, somehow, the repetition drowned out my focus upon it. Or perhaps it was the excitement of what I was going to see.

When I reached the end of the road, Oksana was waiting for me with our backpacks. A huge cloud of steam was mushrooming upwards, much larger than any we had seen before. I was depressingly sure that some “big event” had happened and I had missed it – perhaps a small shelf broke off into the sea – but Oksana assured me that, from her closer vantage point, she hadn’t seen or heard anything unusual.

Daylight was burning, so I hurried her out onto the lava. Someone had glued reflective markers every few yards to mark out a safe path. We alternated between following these and following the many people in front of us. Before long, we came to a sign that said “End of Trail.” I stopped, puzzled, as I could see plenty of people camped out in the distance ahead of us.

Flashback to the visitor’s information center earlier that day: Obviously, one of the most-asked questions at the park must be, “Where can I see some lava?” Right by the door was a prominent display, updated daily, with information about Kilauea’s seaside activity. The rangers had evaluated the area early that morning and set out strict delineations on how far out on the lava one can hike safely. On this particular day, they forbid any hiking out past the “fourth beacon.”

I thought that the “End of Trail” sign must be the end of the safe zone, but there were plenty of people spread out on a small ridge ahead of us. Back in Kona, I had heard, anecdotally, that the rangers either wouldn’t (or couldn’t) enforce the safety rules. I made the assumption that all the people in front of us were risking their safety, but I could also tell that they had a better view… Oksana and I hitched up our bags and pushed on.

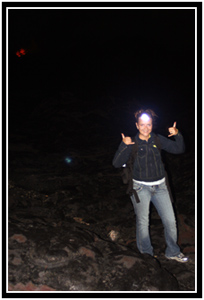

By the time we found a suitable rocky outcrop in view of the lava/sea intersection, it was almost fully dark. There were still plenty of people in front of us, though, so I wasn’t too worried. Except maybe about how I would focus my camera at night. We spread out our stuff, braced our lighter items against the stiff breeze (surprisingly warm and sulfur-free), and set about taking pictures.

And that’s where we sat for the next couple hours. Oksana stretched out on the boulder-shaped chunk rock and kept an eye on the camcorder. I snapped dozens of open-shutter photographs while experimenting with various combinations of ISO and shutter speeds. As the night deepened and the only form of illumination became the mostly-full moon rising over the ocean, red glowing lava began to appear in earnest.

We were well over a mile from the point at which the lava was boiling into the sea. We could neither smell not hear the reaction, but it was nonetheless visually impressive. The red radiance almost continually illuminated the underside of the steam plume and, after awhile, Oksana noticed the hillside speckled with dozens of glowing hotspots. For the entire time I was there, I alternated between shooting those two scenes… at least until someone with a flashlight stumbled into my field of view. The results I spied on my camera’s LCD screen convinced me to set about trying to capture this new paint-by-light phenomenon as more people packed up and made the walk back to their cars.

In the dark, I also noticed three or four blinking lights out in the lava field, the first of which was just near enough to make out. After puzzling out that they were construction sawhorses, I realized that they must also have been the beacons that the park service mentioned in their safety advisories. While the marked trail had ended with the End of Trail sign we had passed, the beacons were placed further out and within sight of each other so that a person could continue on to the closest safe point to the lava.

In our hurry to find a spot before dark, I overlooked the sawhorses completely and we missed our chance to have a better view (and better pictures.) With our flashlights, we probably could have worked our way over to the last beacon, but ultimately decided not to. My heels hurt, the three hour drive back to our hotel loomed over us, and there was no real guarantee that we’d see anything more interesting.

Besides, I was perfectly comfortable where I was. The night was warm, I was happily examining a new photograph every couple minutes, and just seeing the lava had energized me completely. I could have stayed there all night – or at least until my cameras’ batteries had died – if not for the fact that we’d been up since 5am. Although Oksana was happy to stay as long as I wished, I could tell that she was getting tired. At about 9pm, we packed up, turned on our flashlights, and tried to find the trail back to the road.

It took us awhile to locate it because we were walking a little too close to the shoreline. Eventually we realized our mistake and, turning inland, soon intersected the succession of reflectors. From there it was slow but easy going. Before we got back to the road (and then the long walk back to the car) we came across road signs buried in the lava, roving field mice, and the occasional group of beer-drinking partiers. As we passed the ranger’s station, we overheard a conversation about someone that had been out on the lava and had failed to check in. A search was underway, but no one seemed to know what had happened to a certain member of their tour group. It made me feel a little better about our inadvertently conservative stopping point.

We piled back into our rental car and I checked my heels. I expected to find blood-soaked socks, but they were pleasingly dry and stain-free. The skin around the scabs was raw, but otherwise I was okay. I put my Tevas back on and relegated my hiking shoes to the trunk of the car for the rest of the trip.

The drive back Kona was easy, but very tiring. Beside the occasional high-beaming tailgater that had to drive faster than the speed limit, traffic was essentially non-existent. Oksana wouldn’t sleep – she had been taught at an early age that a passenger has that responsibility to the driver – and did her best to keep me awake with conversation. When we ran out of things to talk about, I resorted to a trick I had learned driving across the country: Eating. Trust me; it’s hard to fall asleep when your mouth is busy chewing. I finished off a bag of Combos and a bag of Cool Ranch chips before I was left with just a Diet Coke.

It was almost midnight when we drove into Kona, and the last half hour was the worst. Oksana was trying to keep up her end of a conversation, but she later told me that she was fighting to keep her head up and her eyes from closing. I wasn’t that far gone – if I had been, we would have pulled over and spent the night in the car – but I did make a wrong turn when the road branched in front of us. Fortunately, I realized my mistake after only a couple hundred meters.

We made it back to our hotel and, after unloading the car, we stumbled up to our room and dropped everything onto the floor. We fell into bed and were both asleep within minutes.

The best vacation days are the ones we fill to the brim.

Wow! Awesome entry, you should right a book, really!

No matter where you are guys – you turn any trip into unbeleivable memories for two of you! What a grand vacation, and the photos are as always – outstanding!

Jeff’s idea is good- new Geographic Explorer!

[…] One of my favorite nights on Kona was spent watching lava spill into the sea. The active craters of Kilauea are miles inland, but underground lava tubes transport a steady stream of molten rock to the sea. Where it meets the water, a huge cloud of steam billows upward. Due to a terrible parking space, we had to hurry to get out onto the lava field before dark. […]