There’s an easily-overlooked natural wonder printed on every map of Puerto Rico: “Mosquito Bay.” It’s a regrettably descriptive name, but I like to think the fact it has never been changed is simply a clever cartographer’s trick that keeps the surrounding area undeveloped. The locals on the island of Vieques refer to it as “Bio Bay,” and it’s home to one of the best bioluminescent displays on planet Earth.

The conditions in Mosquito Bay are just right for trillions of organisms, called dinoflagellates, to thrive. Invisible to the naked eye, these microscopic creatures release a tiny burst of light when the water around them is disturbed. When millions go off at once, the water glows blue-green.

Every night, excepting those near a full moon, local companies bring tourists by the van-load to witness the phenomenon. You can’t see it from the shore, so boats are provided. Gas-powered motors have been outlawed, but there are still electric-motor pontoon boats for those that want to be up off the water. Oksana and I chose to take a guided kayak tour.

As soon as we arrived at Villa Coral, our guest house in Vieques, our hosts recommended a small company and made reservations for us that very night. We met our fellow tourists in the empty Sun Bay parking lot while one of our two guides passed around some all-natural, completely-ineffective insect-repellant. We settled up, $30 each, and then, just after sunset, we all piled into a large van and scraped our way along a sandy lane through the mangroves.

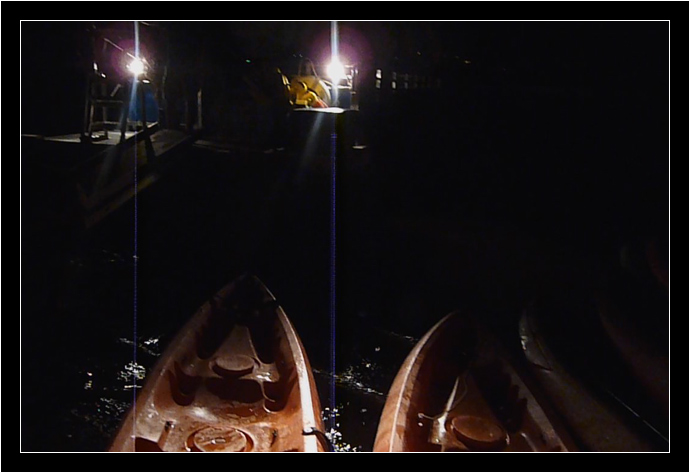

Our time on the shore was mercifully brief, but we still had enough time to learn why they call it Mosquito Bay. Next to us, another company was launching their pontoon boat beneath the glare of twin halogen lights, bug magnets. We stood around in ankle-deep water, swatting ourselves, while our guides equipped us with life vests and paddles. As soon as we were able, we glided out across the water, away from the lights, toward the center of the black bay.

Not more than 40 yards offshore, we began to see the bioluminescence in the water. Every paddle stroke created a pool of glowing green that whirlpooled away behind us. If my wife and I hadn’t been in a twin kayak, we never would have kept up with the group. The temptation to plunge our hands into the water was too great to resist.

Far out in the bay, the only illumination comes from the few houses along one shore and the occasional glare of a passing car. Otherwise: Nothing but white stars above, green stars below.

Our guide forced us to endure a short science talk while we rafted the kayaks together and tied them off to a buoy. Finally, we were allowed into the water. Oksana and I were ready; we had brought our own masks and snorkels. We were the first in and (30 minutes later) the last out.

How can I describe what we saw under the water? Every movement, no matter how small, is a Hollywood-worthy special effect. Pinpricks of light, tiny green stars, trail behind you as you swim. Lift your arm out of the water and sparkling glitter cascades down your skin like a 3D particle-emitter effect. A simple back-float implies the glowing ghost of last year’s snow angel. I imagine a cannonball from the pontoon boat, although antithetical to the tranquility of the scene, would be an impressive emerald explosion.

Perhaps the most impressive sights were the three-dimensional silhouettes created under the surface. A person treading water was reduced to a headless black void, outlined so perfectly you could tell from their curves whether they were boy or girl. A hand, examined up close from behind the glass of a dive mask, was so well delineated you could almost see the wrinkles on the knuckles. On occasion, a fish would dart beneath us, green comets in a galaxy made of liquid. I had the impression that if they swam just a little slower, I could identify them by the shape of their negative space.

As incredible as it was, I’ve actually seen better bioluminescent displays in the ocean. Once, near Ketchikan, Alaska, I witnessed tiny but incredibly bright waves crashing on a rocky beach. One magical night in the Galapagos, I sat on the stern of our boat, anchored off Isla Bartolomé, and watched black sea lion shapes chase black fish shapes for hours.

What makes Vieques’ Bio Bay so special is its unique combination of environmental features. The decomposition of the mangrove vegetation, the temperature of the water, the small channel leading out to the sea, and the lack of development on the shoreline all combine to make a perfect breeding ground for those little bioluminescent dinoflagellates. Each gallon of water in the bay holds as many as 700,000 of the unicellular organisms and the conditions stay the same, year round. There are, of course, other bays where bioluminescent displays are as dependable – many of them nearby in the Caribbean – but Mosquito Bay is considered by many to be the brightest.

My only complaint is that it’s practically impossible to capture the spectacle on film. Consider: When the glare of a full moon is enough to drown out the light produced by these tiny creatures, a photographer’s flash will obliterate it. A stable platform for your camera would make long exposures a possibility, but those are generally hard to come by on a kayak. Most of the better photos found online use either multiple exposures or liberal Photoshopping. Both work well enough, but don’t really capture the effect you see with your own eyes.

Vieques’ Bio Bay is just one of those “you have to see it to believe it” places. Trust me; it’s worth a few mosquito bites.

[…] sporting a perfect new moon, and the flattest, blackest ocean you can imagine. And unlike when we visited the Bioluminescent Bay in Puerto Rico, there were places on the beach where I could set up my […]