The great thing about traveling around the world for a year without a plan is that you can make it us as you go. On our first night in South Africa, I found myself flipping through a National Geographic that was left on a coffee table at our backpackers. There was a feature on the Okavango Delta, with beautiful photos of elephants pushing through marshy waters at sunset. That’s something I’d like to see, I thought.

The Okavango Delta is in Botswana, huh? Oh, and hey, look at the map! Botswana is right next door to South Africa! That’s pretty much exactly how we decided to go.

For a country right next door to South Africa, Botswana is very much a different place. Parts of it matched up exactly with my preconceptions of what an African country would be like (the bus system, the sounds of the spoken languages) and some of it surprised me (3G cellular service, safety.)

A few days before we were set to leave South Africa, we met a couple Canadian girls in Pretoria that were volunteering in Gaborone, the capital of Botswana, for a few months (Hi, Brandy! Hi, Angela!) They offered to let us stay with them at their volunteer house for a couple nights, which was awesome for a number of reasons, not least of which being that we had a couple unofficial guides that had already figured out many of the ins and outs of Botswana society. Their initial help with things like the bus rank were invaluable.

The Bus Rank

When we saw the bus rank for the first time, I thought, now we’re in Africa!

Setting aside the oddities of the private cab system, we didn’t have to make many adjustments to adapt to the transportation in South Africa. We could still find information about bus tickets and schedules online. If we didn’t want to buy our tickets straight from their web pages, we could show up at the bus station and browse through the various offerings at the offices there. Not so in Botswana.

When we first showed up at the bus rank, it was late afternoon, the strong Kalahari winds were kicking up huge clouds of dust, and there were hundreds of people milling around. Dozens of buses were parked bumper-to-bumper in 15 parallel lanes, each about as long as a football field. We walked around the perimeter trying to find an office, ticket salesmen, or any information at all. There was none.

Oksana stopped and asked the owner of a fruit stand how to find a bus to Maun, our next destination. The vendor just pointed to the buses and said, “Go ask.”

So we did. There were no buses to Maun. At least not in the afternoon. Some random guy – who, in his defense, seemed to know what he was talking about – told us to come back in the morning. “When?” we asked. 5:30, maybe 7:00. Since the answer to the question of how long the bus would take to reach Maun was equally vague, we resolved to get there early and wait around, if necessary.

The next day, the taxi we’d arranged to pick us up at the volunteer house at 5:30am arrived at 5:20am, instead. This was a good thing, because when we arrived at the bus rank and our driver embarked on the same question-and-answer quest that we had the day before, a bunch of the kids told him the 5:30 bus to Maun was just about to leave. They sprinted alongside our cab as he sped down one rank and swung his taxi directly in front of the bus. The bus driver immediately started revving his engine and honking his horn at us. I paid up while Oksana pulled our giant bags from the trunk and as soon as we clambered aboard, the bus was in motion. Apparently, even without posted times, random guys really do know exactly when the buses depart.

Safety

The buses available in Botswana are not tourist buses. Our bus to Maun was fairly standard — no AC, no mounted screens showing unwanted movies, and the typical reclining seats had been removed so that rows of straight-backed chairs could be welded to the floor, five seats per row.

I can’t say it was comfortable, but it wasn’t the worst bus we’ve ever been on.

Strangely, despite the shoddy setting and the fact that we were the only tourists aboard, I felt much safer on this bus than I did on the ones in South America.

Oksana and I always transfer our most valuable or irreplaceable items (laptops, cameras, passports) from our big backpacks to our day bags whenever we ride on a bus. That way, if our main packs go missing, or if someone decides to root through them when they’re out of our sight, we won’t lose anything too important. (For what it’s worth, I think the odds of that happening are very slim, but if nothing else, it lets us relax a little.)

I’ve been on trips through South America where students have had their wallets taken out bags stored in the overhead bins. On one trip through Peru, my friend had his camera and lens taken out his camera bag. He didn’t notice until well after he’d left the bus because the thief had replaced them with two tiny bottles of water, filled to the brim and resealed to prevent them from sloshing around. Somehow, they’d managed to make the switch while the camera bag was on the floor, between my friend’s feet.

More often than not, Oksana and I pass whole bus rides with our heavy day packs sitting on our laps. Whenever mine starts to get too heavy, I just remind myself how much I’d hate to lose a hard drive full of our photos and videos…

Passengers in Botswana were quite comfortable putting their bags and, in some cases, their purses out of sight in the overhead racks. I got the impression that our bags were much safer buses in Botswana than they were in South America, though I wasn’t going to test that by putting my bag above us and there wasn’t enough leg room to fit them on the floor by my feet. Fortunately, for most of our ride to Maun, we had three seats to ourselves and rested our packs on the chair between us.

Taxis

Cabs were much easier to identify in Botswana than they were in South Africa, which was a relief. There was no coordination in the color of the cars themselves, but all the official cabs had blue license plates. I thought that was a fairly clever and simple way for the government to let people know which cars were safe to flag down.

In bigger places like Gaborone, there were two types of taxis: Shared and special. Special taxis would take you wherever you wanted to go (after agreeing on a price.) Shared taxis ran a set route and if they had a seat available you could flag them down. For a set price you could get out anywhere along the route.

Combis

Like many other places we’ve been, Botswana has a thriving minivan fleet. In smaller towns like Maun, they hang out at the bus rank and depart as soon as they fill up. They run set routes and can take quite a bit longer than a taxi because they’re constantly taking on and letting off passengers.

When we stayed at the Okavango River Lodge, which is about 12km outside Maun, it could take us a half hour to make it into town on a combi. On the plus side, it only cost us 3 Pula each (whereas a taxi cost us 30-40 Pula.)

Combis can be crowded and uncomfortable, but you get a chance to meet new people and learn more about a culture when you take them. If it’s easy enough for us to figure out where they’re going, as it was in Botswana, it’s often our preferred form of transportation.

Wealth

When we were about to leave South Africa and mentioned that we were moving on to Botswana, people’s first reaction was usually, “Oh, you’re going to love Botswana. It’s so much safer than South Africa!”

South Africa, while considered a well-to-do African nation, does have a bit of a crime problem. We were extra careful while we were there, so we saw no trouble, but we heard horror stories about Johannesburg. It’s not that other countries, like Botswana, don’t have any crime; it’s that the crime in South Africa can be so bloody and violent.

One of the reasons Botswana may be safer is its larger middle class. South Africa has one of those huge disparities between the haves and the have nots that can lead to desperation in the poor. It’s easier to rationalize turning to violent crime when you’re struggling to survive. Resource-rich Botswana, on the other hand, has the largest middle class in Southern Africa. Of course, their standard of living is more like Mexico than the United States, but somewhere around 60-70% of the population lives comfortably in the middle class. Come to think of it, that’s probably why the buses felt safer.

Demographics

It should probably go without saying that almost everyone in Botswana is black. To my eyes, everyone was the same, but there were at least five different ethnic groups living in near the Okavango Delta alone, so the local divisions were obviously lost on us. Suffice it to say there were places where white visitors were rare. Some people were not shy about staring at us.

It didn’t bother me at all. I’ve been to place in South America where the same thing happens. It just made me realize how much of an oddity South Africa is with its sizeable (for Africa) white population.

Weight

When we were staying on a riverboat in the Okavango Delta, we found ourselves talking about fishing with some of the locals. Fishermen come from all around to catch the Ngwesi, or tiger fish. Of course, coming from Alaska, we had our own fishing stories to tell and people were curious. When we were talking about salmon and halibut, someone stumped us with a question:

“How many cageys?”

“’Cageys?’”

“Yeah. How many?”

Took me a second to figure out that he wasn’t after a measurement of the fish’s evasiveness or cleverness. “Cageys” is “KGs,” or “kgs…” Kilograms!

Fishing

Speaking of fishing, Oksana and I got to try our hand on the Okavango Panhandle and we each managed to catch a tiny Tiger fish. Strangely, every fishing pole we were handed had the reel mounted in it the wrong direction. I’m right handed, so I expect to hold the pole with my right hand and reel in the line with the left. These casting poles had the reel’s handle on the right.

When I throw a rock with my left hand, the motion is about as fluid and accurate as the arm of particularly talented preschool girl. I wasn’t about to risk casting a lure, left-handed, with people around. I had to switch to my right hand to cast, then quickly switch the pole back to reel in the line.

Our guide, who was also right handed, seemed very surprised that the reels weren’t set up the same way in the United States. I joked that it must be because we’re in the southern hemisphere. When in doubt, blame the Coriolis Effect!

Language

The main language in Botswana is Setswana. We didn’t learn much while we were there and the only thing I can remember now is the word for hello: dumela.

Oksana and I quickly picked up on and puzzled over a couple sounds that people made in the normal course of conversation. I’m sure you’ve heard one of those African “clicking” languages on National Geographic or something. Well, Setswana isn’t like that, but people do issue a clicking sound every once in awhile. Oksana thinks it was a sort of negative reaction, sort of like exclaiming, “No way!” or “I call bullshit!”

Another sound we often heard was used, we think, as a reaction to something surprising. I can only describe it as a “high bird sound.” Sort of a vocal “ahhhh!” that is pitched very high for the first instant then descends: AAaahhh…! (I couldn’t imitate it for you if I wanted to.)

“You know, in Alaska, people still catch halibut that weigh 100 cageys.”

“AAaahhh!”

“Yep. True story.”

Weather

The Kalahari is nothing if not consistent, at least in June. It was a little chilly at night, but the days were always warm and sunny. In fact, after a freakish thunderstorm rolled through on our first day in Gaborone, we never saw a single cloud in the sky for the entire rest of our stay in the country.

Cellular Networks

Botswana seems to have a very competitive cellular industry. Cell phone stores are everywhere (as they are in pretty much every other country), but I saw some cool things here that I hadn’t seen elsewhere.

First, SIM cards are dirt cheap! You can pick them up practically anywhere. Our bus was stopped at a police checkpoint and we were forced off it so they could do a cursory sweep of the interior. All we had to do was step out, walk past a cattle guard on the road, wait for the bus to pull forward, and re-board. In the meantime, I decided to buy a drink from a roadside vendor.

The woman selling sodas from an ice-filled cooler had only a plywood table along the side of the road. Next to a cooler was a stack of phone cards and little plastic pouches containing SIM cards. 1 Pula, or about 15 U.S. cents, was all you needed to get your own phone number in Botswana!

I also saw advertisements for a pretty cool 3G device. Rather than a 3G phone or a 3G USB stick for your computer, this looked like a full-fledged 3G router for your home. Set the router up with a SIM card, pay the monthly fee, and suddenly you have both a phone and a wi-fi connection for your home or office. No installation necessary, just plug it in and go.

I wonder why I haven’t seen something like that for sale in the U.S. The closest I can think of is a WIMAX connection. I sort of like the idea of a 3G router you can plug in anywhere under within range of a cell tower. May not be super fast, but it’d much easier than setting up a full-fledged wi-fi router or tethering to your cell phone (especially for multiple devices.)

Drugs

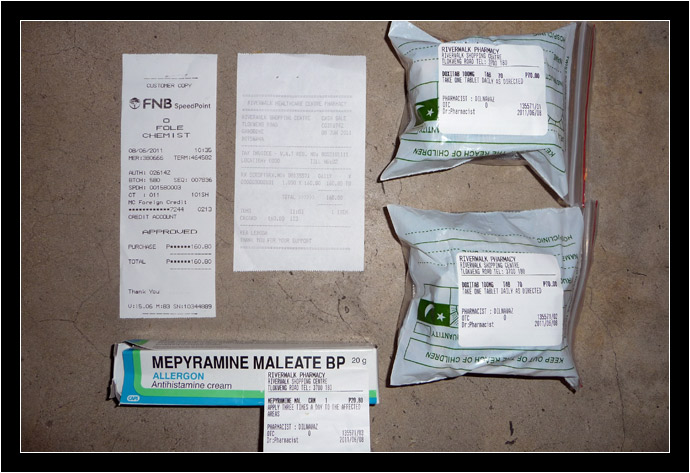

Another reason to be thankful for running into those Canadian girls: They clued us into a Canadian doctor who had an office in a nearby mall. Oksana and I decided to pay her a visit before we left Gaborone to ask about something we were hoping to avoid: Anti-malarial medication.

I wasn’t hopeful; I’d heard horror stories about Lariam, the anti-malarial that causes realistic and terrifying nightmares. Everyone I’ve ever met that has tried it, had quit their course they thought that dealing with malaria would be easier. After talking to Doctor Kahn and doing our own copious research online, we decided to ask for a prescription for either Malarone or Doxycycline. We got both.

Which was a good thing. The CDC site informed us that we’d be at risk from the time we hit the Okavango Delta all the way up to parts of the Nile in Egypt.

Prescription medication is much cheaper than in the U.S. When we realized that each Doxycycline pill cost only about 15 cents (meaning that a whole two-and-a-half month course cost us only about 11 bucks each!), we asked about some of the other things we opted not to pay for in the States. Before we left, we’d also been inoculated against polio and had prescriptions for an epi-pen, and two prescription-strength antihistamine and steroid creams.

I’m kind of wishing we hadn’t spent so much on vaccinations before we left. I’ll bet we could have saved hundreds of dollars by waiting.

Men’s Room Behavior

I found it passing strange that, in the men’s room, guys were remarkably shy. Normally, guys walk up to a urinal, do their business and go on their way. In the U.S., there’s sort of a “personal space” issue that results in an unspoken agreement: If there are other urinals available, don’t select one right next to someone else. But when, say, a big movie lets out at the cinema, everyone shoulders up without complaint.

In Botswana, the first guy to select a urinal would invariably choose the one on the very end, and even so, he would face the corner and hunch his shoulders way over before letting loose. Sometimes I would enter a bathroom with someone already doing their business and as soon as I selected my urinal, he would turn away from me. No idea what’s up with that! Do think they I’m trying to sneak a peek? Are they embarrassed about their size? Or perhaps an STD? No idea, but it kind of creeped me out. Like they were trying to hide a golden penis or something.

Could the HIV/AIDS problem be a part of it?

HIV/AIDS

The single biggest health issue in Botswana has to be HIV/AIDS. Some estimates say that 25% of the population is infected. One in four people.

(I skimmed a journal that claims that the life expectancy in Botswana before the advent of AIDS was 65. It’s 35 today. I’ll be 39 next month, which means I’ve outlived the average Motswana by 4 years. That’s insane!)

I can’t imagine what sort of affect that has on a culture. Apparently it’s not causing the kind of fear that I would expect because everyone will tell you that many people in Botswana still have multiple sex partners.

I can remember back in the 80s when AIDS was a huge scare in the United States. I was in middle school and we were forced to sit through all manner of serious conversations about how we can keep ourselves safe from AIDS. Our teachers, counselors, and even hired speakers at big assemblies drilled monogamy and protection over and over. I wonder if Botswana is too conservative. Do they start teaching Sex Ed in the 4th grade, like we do in the U.S.?

One visible piece of education – the only visible piece I ever saw – was the “sexual networking” billboards all over town. “It’s shocking who you can find in your sexual network!” I see what they’re trying to say – If you sleep with someone, you have no idea who they may have slept with before. However, I can’t help but think the term “sexual networking” is too innocuous, perhaps even bordering on risqué fun. Sounds Facebook for swingers, you know?

Throughout our stay, we learned bits and pieces about the culture that gave us small insights into why simply teaching kids to use condoms might not be enough to conquer the AIDS problem in Botswana.

Botswana still has a strong cultural hold on the dowry system. Men who wish to ask for a woman’s hand in marriage are expected to have a certain number of cattle to give to her father. While Botswana may have a lot of beef, but I doubt most of the male population has set aside some of cows for marriage. If getting married is so complicated, you can imagine that pre-marital sex would increase.

Also, marriage infidelity is a big problem… and it’s not necessarily the men who are at fault. More than one person told us that it’s the women who slept around.

With fathers who won’t give their daughters away for free, and women who are assumed (justly or otherwise) to be unfaithful after matrimony, is it any wonder that a large portion of the population remains unwed and polygamous?

There’s a “why buy the cow when you can get the milk for free” joke in there somewhere.

McDonald’s

There’s no McDonald’s in Botswana, which was a bummer for our little project. But I read something interesting about why the golden arches haven’t made an appearance yet. Botswana’s government is very strict about the health of their cattle. The country is segmented by huge tracts of land, divided up by miles and miles of fences. The roads we drove on had periodic checkpoints with anti-cattle gates to keep cows were they’re supposed to be. I guess they’ve had a few hoof-and-mouth disease scares that required quite a few head to be put down.

Anyway, the government is very proud of their beef and when McDonald’s came knocking, they said sure, come on in. Just one thing: Your burgers have to use 100% Botswana beef. Well, McDonald’s has their own manufacturing and distribution plans and having to alter them for one country didn’t make much sense financially. (Plus, if there was another huge hoof-and-mouth outbreak, it’d cripple the McDonald’s franchises in the country.) So… that’s why we couldn’t have a Big Mac.

No idea if it’s true. Sounds plausible, though.

Food

After South Africa, food in Botswana was noticeably cheaper (especially the meat) despite having the exact same supermarket chains. For us, it was a relief. In South Africa, we’d taken to buying PBJ makings in grocery stores to save money. In Botswana we were free to eat at restaurants again.

Diet Coke

Aluminum cans are heavier in Botswana. I noticed with Diet Coke cans, because after drinking a few thousand of them over the years, I’m familiar enough with how they should feel. All the soda cans in Botswana seemed the same, however. I assume it has something to do with manufacturing plants with less precise can-making equipment, but who knows?

It was annoying. Every time I finished a drink, I always thought there was one more sip left in the can.

Mopane Worms

Mopane worms are the caterpillar stage of the Emperor moth. They are a bit of a delicacy in Botswana; you can even find a picture of one minted on the 5 Pula coin. We saw big bags of dried, black Mopane worms for sale at the bus rank in Gaborone. We did not buy any.

Alrighty, here is the long promised comment!

First, I should mention that I changed the name of my blog which means your link to me doesn’t work 🙁 Here’s a new one http://brandysbustlings.blogspot.com/ (Fixed it! -Arlo)

The Bus Rank

The Bus Rank is an experience like no other. The day I had to go there, by myself, to buy bus tickets (there actually are a few buses that you can buy tickets for) will go down as one of the scariest days of my life. You two were lucky; your bus left as soon as you arrived. We were told to arrive at 5:00 p.m. and that we would board at 6:00 p.m. We left Gaborone at 9:00 p.m. “No Hurry in Africa”.

Also, it’s always the random guy that knows what he’s talking about. That’s one of the things I loved best about Botswana. If you didn’t know something, you just asked someone, anyone. As we prepared to climb Kgale Hill for the first time, it was the random guy walking down the road who assured us that the baboons were not dangerous. I’m pretty sure they are dangerous if you piss them off, but we didn’t so they weren’t.

Safety

Did everyone on your bus have a massive blanket in addition to whatever else they were carrying? On our bus up to Kasane, it sure seemed like everyone did. Odd, I thought, until I realised how cold it gets at night on those buses.

The problem with people stuffing everything in those overhead bins, is that they stuff everything in those overhead bins. Then, at 7:00 a.m. passengers like me, awaken to a suitcase falling on their head.

As for safety in general, I have one thing to say. Botswana is all safe and comfortable until someone steals your cell phone and bites your hand in the process. That is all.

Wealth

It amazed me how the class differential was so blatant in South Africa, but Botswana remained seemingly untouched by that disparity. The reason, as non-pc as it may sound, is due to a lack of rich white people. At least that’s what I would attribute it to. The lack of large haves and haves not populations was comforting, until I spent some time in Maun and saw it happening there. Those rich white people I mentioned run the city center in Maun, while the poor black people struggle to survive in the village peripheral.

Demographics

It’s kind of like living in a zoo. I loved being the minority in Botswana. That was one of the experiences I was most looking forward to. Being the one stared at all the time gave me some insight into how the students I was working with would feel when they arrived in Canada.

Language

That high-pitched sound to which you are referring is “Aeish” with a definite focus in the upper vocal register on the first three letters. It took me at least a month after returning to Canada to stop saying it when something surprised me in an “I don’t believe it” kind of way.

Drugs

Wasn’t Dr. Khan just great?! Her counterpart however, (I don’t remember his name) told me I didn’t need stitches after stabbing myself in the hand with a serrated steak knife. I’m pretty sure I should have gotten stitches, but I have a pretty wicked scar now. I tell people that a bush baby bit me!

Men’s Room Behavior

I was never in a men’s room, but I can tell you that the women definitely aren’t as shy. Most of the time, I would walk into a bathroom to see a woman sitting on the toilet going about her business. Not because there weren’t doors on the stalls, but just because they didn’t really care who saw them. I suppose those actions add some literal meaning to ‘pubic restrooms’.

And toilet paper…I have to mention toilet paper. There was never any, anywhere. I carried toilet paper or Kleenex with me everywhere I went. Oksana may have noticed this a lot more than you, Arlo.

HIV/AIDS

I spent a decent amount of time with an HIV/AIDS expert while in Botswana. Bots is actually a success story in terms of HIV treatment. In the last decade (I think) they’ve cut the mortality rate in half. This is happening, of course, because Botswana was one of the first countries to implement free anti-retrovirals (ARVs) to people with HIV. The stats that are pouring out of Botswana look great and they are…sort of. The problem lies in the fact that the incidence rate isn’t changing nor is the number of cases (there’s a fancy name for that too, but I can’t remember it). Botswana is doing wonders in terms of treatment, but nothing in terms of prevention. In fact, the government doesn’t even have any budgetary money set aside for prevention strategies. As for Sex Ed in schools, while I am not positive on this, I am quite sure that it doesn’t exist. People are still very unwilling to talk about sex; HIV/AIDS is still highly stigmatised.

In terms of who is to ‘blame’ for the promiscuity issue. All I know is that we were ‘warned’ on numerous occasions that the men of Botswana cast a wide net. It’s likely the same for the women. You know, the old fish in the sea cliché. Well plenty of fish…wide net in the hopes of catching something. Pun totally intended there. I won’t even get into the numerous stories I have about being hit on and proposed to. What I will say is that one especially forward cab driver was pretty taken aback when the four Canadian girls he wanted to marry started asking him how many cows he had to offer in exchange. He only had ten (which I’m pretty sure translates to zero) which clearly wasn’t enough when the going rate for a Canadian girl was at least 150!

Diet Coke and Mopane Worms

Just because I can, I must inform the reading public that Diet Coke does not actually exist in Botswana. It’s called Coke Light, but it tastes and the packaging looks exactly the same. Annoyance is indeed thinking you have at least one more sip when the can is actually empty. I never did get used to that, even after four months. As for Mopane worms, if someone asked me what I regret not doing in Botswana, I’d say trying Mopane worms. I ate cow intestine after all; I doubt Mopane worms could have been any worse.

Ke Rata Botswan (I love Botswana)

Turning away from you in a urinal is a sign of African respect, and you would be expected to turn away too. Not to do so is rude and a sign that you weren’t brought up properly. The rule applies to SA too. If someone doesn’t look directly into your eyes, but rather at the floor, that is also a sign of respect. it is considered rude to look up into a stranger’s eyes.