Tanzania started off bad for us and then went downhill from there.

It all began with what was supposed to be a 27-hour bus ride from Lusaka, in the middle of Zambia, to Dar es Salaam, on the Tanzanian coast. We knew it would be a nightmare, but convinced ourselves that doing it all at once would be better than trying to find a place to spend the night somewhere along the way. That was probably a mistake. Due to a couple breakdowns and a few of those who-knows-why bus stops in the middle of nowhere, our 27-hour bus ride turned into a 34-hour one. That may not seem like much of a difference, but just try to imagine spending an extra work-day on a hot, sweaty bus after you’ve already spent a day and a night in the same seat.

When we finally reached Dar es Salaam, we missed our stop at the main bus terminal. Fortunately, the next stop wasn’t too far along and even though it was after 1am, we managed to find a taxi driver who was willing to take us to a hotel… for just three times the normal price. Of course, the hotel we’d picked from our guidebook was full. Our second choice was also full, but the night manager said we could have one room as long as we vacated it before 8am. After showers, that left us with barely five hours for sleep, but we took it.

The next day, we looked around Dar es Salaam and decided that there wasn’t much for us there. Our plan, as it so often does, changed. We opted to spend our time in on the island of Zanzibar, instead. If you’ve been reading along, you’ll remember that’s where we were mugged at machete-point.

If you haven’t read our story about getting mugged at machete-point on the beach in Zanzibar, you totally should. It has a few more details about life in Tanzania and Zanzibar, plus I promise that it’s a much more interesting and entertaining than this blog post!

The whole reason for going to Tanzania was to climb Kilimanjaro and we had to back out of that plan because it was just too expensive. Thinking back, I wish we had at least left the coast to see the mountain. We could have gone on another safari, this time in the Serengeti, and seen some of the big herds migrating. We could have checked out the Ngorongoro Crater, or even climbed one of the lesser peaks in the area. Lots of regrets, lots of reasons to go back.

In all, our time in Tanzania amounted to just 18 days. We left with some disappointing memories, but also some great stories.

Pronunciation

How do you say “Tanzania?” I’ve always pronounced it with the emphasis on the second-to-last syllable: tan-za-NEE-ah. I once asked a Tanzanian if anyone ever said it that way and laughed at me. They say: tan-ZAN-ee-ah.

Swahili Time

We were used to setting our clocks forward or backward when entering a new country, but Swahili Time was so conceptually different from western culture that it caught my attention right away.

Swahili Time starts when the sun rises. Since Tanzania is close to the equator, this usually happens right around 6am. But sunrise is not at 6am. It’s at 0 O’clock Swahili Time! The clock starts counting up from there, so 7am is 1 O’clock, noon is 5 O’clock, and the sun sets about twelve hours later at… 12 O’clock! (I assume they continue counting in the military/24-hour clock fashion until the next sunrise, but I don’t really know.)

Our guidebook warned us to make sure we understood what time was being used when we were looking at bus and ferry schedules, but to be honest, we didn’t see anything other than Greenwich Mean Time (shifted +3) being used. I would guess that in this age of globalization, it would be difficult, if not impossible, for a country to maintain its own time system. Still, in the rural areas where the people have no interactions with the international community, let alone the nearest city, I can see how this system of counting the hours makes a lot of sense.

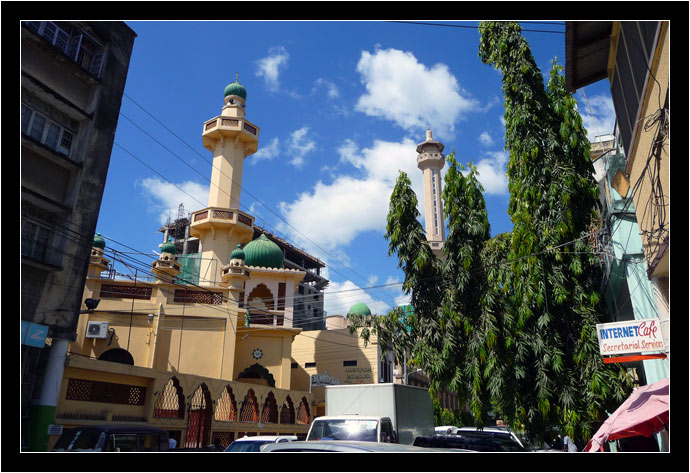

Islam

Tanzania was the first Muslim country we’d visited and there were huge cultural differences everywhere we looked. Mosques dominated the skyline, men dressed in long flowing robes, and women were often covered head-to-toe in black burkas.

Our hotel room had a pair of those glass-slat windows that can never truly be closed, so over the course of a few days, we became very accustomed to the calls to prayer. Many times a day, starting as early as 5am, bullhorns attached to the tallest mosque spires would come alive with the warbling sounds of Islamic singing. Presumably, this was to remind people that it was time for them to come to the mosque or, at the very least, put down what they were doing and pray. I saw “presumably,” because I can’t say we saw much of a change in people’s behavior out on the street.

At first, I resented that the calls to prayer woke me up every morning before dawn, but like the post office truck that drove up to our apartment every damn morning back in Alaska, my sleeping brain quickly learned to tune it out.

Diet Cokes

I know I keep bringing up Diet Cokes in these “Thoughts On…” blog entries. Look, it’s just a “write what you know” thing, okay?

It took us awhile, but we found a pretty decent grocery store in Dar es Salaam. In a cooler full of soft drinks, they had a shelf each for both Diet Coke and Coca-Cola Light. Up until I saw them side by side, I always assumed they were the same thing. However, this store was selling the cans labeled as Diet Coke for twice the price. Intriguing!

Ever since we left home, Oksana and I have noticed that the Diet Cokes – Sorry, I mean the Coca-Cola Lights – we’ve been drinking have tasted a little… off. Hard to put a finger on what it is that tastes different. I’ve described it as a slightly “fruity” flavor before, but that’s not really an accurate description. Whatever it is, it leaves an aftertaste that I don’t especially like.

I wanted to do a taste test to find out if the difference in price was because the Diet Cokes were authentic imports or something, but I couldn’t bring myself to pay over two dollars for a can of soda.

It could have been that the cost difference was in the can itself. The Diet Cokes looked like a normal “pop-top” can to me. The Coca-Cola Lights we ended up buying had the old style pull tabs. Oksana was floored. She kept saying, “I haven’t seen those in at least 12 years. And that was back in post-Soviet Russia!”

(Side note: We’re in Bulgaria as I’m writing this and it’s the first time in a very long time that the Diet Cokes have tasted normal to us. They’re labeled “Coca-Cola Light.”)

Buckets

Every bathroom in Tanzania (tan-za-NEE-ah!) had a little bucket in it, usually perched on top of the toilet tank. I have no idea what they’re really for. Oksana thought they were probably a poor man’s bidet.

Post Office

I spent a little time at the post office in Dar es Salaam. Believe it or not, it was kind of a cool place to hang out.

First, I should mention that the Tanzanian postal system seemed rather cheap in comparison to other countries we’d visited. I think it may have been the first place that cost under a dollar to send a postcard back to the U.S.

The post office we visited was also outfitted with an entire internet café. Compared to the mismatched computers and bulky CRT monitors in other Dar es Salaam cafes, the new-ish Dells and flat-screen LCDs made for a nicer online experience. Plus, it only cost about one U.S. dollar per hour online. Pretty darn cheap.

At the counter, they also had signs up advertising the sales of SIM cards for your cell phone. Very progressive for a postal system, I thought.

It’s interesting to see how institutions are embracing technology in order to survive. In the U.S., it’s libraries that are embracing public-access internet terminals, which seems like a good fit to me. I doubt that Tanzania has the same book-loaning infrastructure that we do, so perhaps the postal service is the next most logical place to give people access to the internet.

Come to think of it, maybe something like this could help save the U.S. Postal Service.

Power outages

We were in Tanzania for almost three weeks and every single day we had a power outage. It was not abnormal for us to have 10 separate outages a day. Sometimes it was only for a few minutes, but there were times where it could be out for hours and hours.

I heard different explanations for why. Damaged equipment was one. Not enough power to go around was another. If it was rolling blackouts, though, there wasn’t ever any warning. There was no scheduled time of the day you could plan around an outage in your area.

On Zanzibar, they said there was only one underwater connection to the mainland and they were at the mercy of Dar es Salaam. We were often told about the previous summer when the power had been out for a three entire months. No power at all during the time of year when the temperature hovers between 90 and 100 degrees Fahrenheit every day.

I don’t know how the people of Tanzania are expected to get anything done with an electric grid in such disrepair. Actually, I guess I do. Every business of any size has its own generator. When the power goes out, you can hear dozens of the gas-guzzlers coughing to life on each and every block. Makes for a noisy city.

Traffic

So far, I believe Dar es Salaam has the dubious honor of being the city that I’d least like to drive through on this trip. Traffic there was insane.

Four way intersections on narrow streets were the norm and, as far as I could see, stop signs and stop lights were practically nonexistent. This meant that during the day, long rows of cars would snake back from all four streets as drivers jockeyed their way through the intersection. I could see no system at work except, perhaps, “fortune favors the bold.”

If we had rented a car to get to Dar es Salaam, which we’d discussed at one point, I’m not sure what I would have done when we got there. Getting injured in an accident wasn’t much of a concern; the traffic was much too sluggish for that. I’d just be worried about denting up the rental car. The only way to get through an intersection seemed to be to force your way and there was never more than a few inches to spare on either side of the car.

Good thing the taxis were relatively cheap.

Crosswalks

On the bigger streets, there were a few stoplights, even some lighted walk/don’t walk signals. I wish we’d recorded a video of the little, green, animated guy on them. When it’s safe to walk, he has a nice, gentle stride. As the stoplight gets closer to changing, however, his gait starts to increase. Just before traffic is set free, he’s practically sprinting – just like what you should be doing if you’re only half way across the street by that point.

Laundry

Oksana had the window seat on the 34-hour bus ride and she noticed that people didn’t hang their clothes to dry, but rather they spread them out on the ground. Just an observation.

Speaking of laundry, we had a difficult time getting our clothes washed in Tanzania. Our first hostel, The Safari Inn, was okay because they had a laundry service. I wouldn’t say our clothes came back super clean, but they were nicely pressed and folded.

Our lodge on Zanzibar didn’t have any laundry service at all and didn’t recommend we take it to the village for washing, either, because everything there is hand-washed and often brutal for some fabrics. We went the week without.

When we returned to Dar es Salaam, we stayed in a different hostel, The Jambo Inn. They didn’t have a laundry service, so we asked them were we could take our Zanzibar-dirtied clothes. They gave us directions to the only place around. It turned out to be a dry cleaners. They’d wash our clothes for us, sure, but they charged by the item, not the kilo. With so many little things like underwear and socks, we were looking at paying 15 times what we paid at The Safari Inn.

So… we walked back to The Safari Inn, even though we weren’t staying there, and asked if they would wash our clothes for us. At first, they said no. It was a service only for paying customers. They didn’t have any better options for us, either. As we were about to depart with our sad, puppy-dog faces on, they said we could talk to the manager if we wanted to.

We did. And at first it didn’t sound like he was going to help us, either. He asked why we weren’t staying with them again after returning from Zanzibar. “We tried!” Oksana told him. “You didn’t have any vacancies!” It was a half truth – we did try calling, but only after we couldn’t get through to The Jambo Inn…

The manager explained to us that the laundry service wasn’t profitable for the hostel. He set up the service for the Swahili employees that cleaned the rooms. It was a way for them to make a little extra money, he said, so that they were less inclined to steal from the rooms.

I admired that, actually, and completely understood his hesitation. We thanked him for explaining things to us and were about to leave when he told us to hold on. He called down one of the cleaning staff and asked them if they wanted to do the laundry for us. He did, so we left it with him and picked it up in the next morning.

Sure beat washing things in the sink and hanging all those clothes to dry in our own room…

Hanging Leaves

In Zanzibar, we noticed strings of leaves hanging over some doorways. Don’t know why, or what they represented.

Cheap Labor

It always amazes me to see the effects of cheap labor costs. In Peru, I watched as a couple guys took apart a four-story, cement building – slowly – with nothing but a pair of sledgehammers. In South Africa, many of the crop fields were harvested by hand. When we were on Zanzibar, I saw another fascinating example.

As we were waiting in line for a ferry to take us back to the mainland, I watched as the huge catamaran pulled up to the dock. As soon as its lines were tied, two guys stripped down to their shorts and hopped into the water alongside it. Wearing masks (but no snorkels), they set about cleaning the hull along the waterline. One had what looked to be a washcloth, the other nothing more than his bare hands.

They laughed and joked while the worked, shouting up at people on deck and others standing on the dock. They didn’t seem to mind the job at all, but with the ship in port for only an hour or so, I don’t know how much of the hull they were able to scour clean. The ferry runs two or three times a day, however; they probably go swimming every time.

Language

All the African countries we traveled through had plenty of people who spoke English, but Tanzania might have placed a little less importance on the language. Perhaps that’s because Swahili is a better common language for them to learn, or perhaps it’s just because English isn’t taught as much (or as well) in the schools. That’s not to say we had any difficulty getting around; we didn’t.

We couldn’t help but pick up a few words of Swahili while we were there because everyone said one of two words to us every time we passed: Jambo or karibu. We picked up jambo by context, and used it quite often ourselves: It’s “hello.” We had to ask what karibu meant: “Welcome.”

Strangely, “You’re welcome,” was one bit of English that many Tanzanians used incorrectly. Well, not incorrectly, just literally. When you walked into a store or restaurant, the owner would smile to you and say, “You’re welcome.”

For what? I’d think for a split second. Then I’d realize what they were actually saying: You are welcome here.

One phrase I was completely unprepared to hear was hakuna matada. How many of you reading those words just pictured an animated meerkat and a warthog singing a duet? I never realized that one of the most memorable lines from The Lion King came was an actual saying in Swahili.

The first time I heard it, I think I was ordering something to drink at a restaurant. Probably said something like, “Would it be alright if we got one large beer, but with two glasses so we can share?”

“Hakuna matada,” he replied, and walked off. No worries.

The only other Swahili phrase I remember is sort of related to Hakuna matada, in feeling if not in translation. It’s pole pole, which brings us to my favorite (and very educational) story about Tanzania.

Wait! I just remembered one more! We learned how to say “rambutan” in Swahili, too. It’s mshokishoki!

Pole Pole

When we were in South America, we joked about “Latin American Time.”

“When does this bus leave?”

“Now.”

“Right now?”

“Yes, right now! Buy your ticket, or you’re going to miss it!”

We buy our ticket, get on the bus, and then wait half an hour or more before it departs. Everything seemed to operate like that; no matter what time was given, in reality everything was always más tarde.

In Tanzania, and most especially on Zanzibar, pole pole is más tarde. Chill out! Slow down! Pole pole.

Two stories to illustrate this point, both told to us by an Italian expat, Renato, who now owns and operates The Twisted Palms Lodge, with his wife, on the back side of Zanzibar:

In starting up their business, Renato and Laura needed to buy certain things for the lodge. The first was a set of uniforms for their employees. They wanted to have colorful, island-style shirts with the Twisted Palms logo silk screened on the front and on the sleeves. They took their artwork to a graphic artist in Stone Town and gave him a few days to create a sample for their approval.

When they returned a week later, everything looked great… except that he had used the same logo for both shoulders. Since the name of their lodge was a part of the artwork, the text was printed in reverse; the only way you could read it was in a mirror.

When they pointed this out to the graphic designer, he seemed completely taken by surprise. Not only did he not realize that the text was backwards, he didn’t share their belief that it was a problem.

The Italian expat didn’t think he should have to pay for the flawed T-shirt, but felt he should compensate the designer for his time, especially since he still needed five or six (correctly designed) shirts printed up. When he offered to pay for the work, but not the shirt, the designer thought about it for a minute and then said he’d rather just give him the shirt and the work for free… as long as he never has to see him again.

Second story, same protagonist:

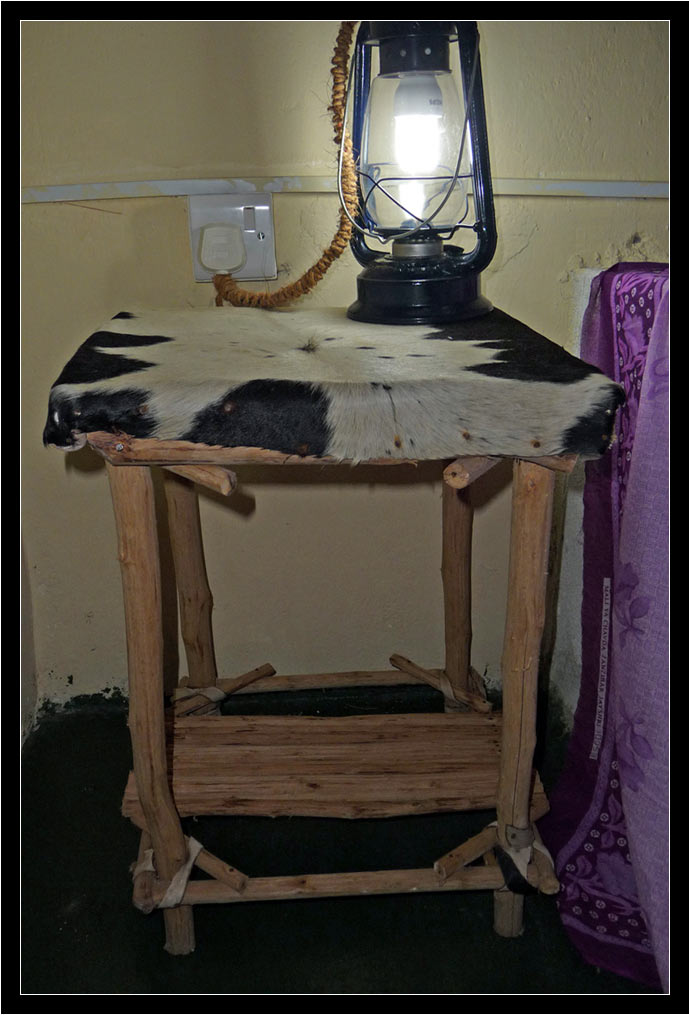

Our Italian friend decides he needs to have nightstands for each of the rooms in his new lodge. He finds a man known for his woodwork and use of local materials and asks him to build a small table. “How much do you think something like that will cost me?”

“10,000 shillings?”

“Okay, sounds good. I’ll be back in a week.”

He comes back, the table is complete and he finds the work to be good. He pays the man 10,000 shillings and says he wants 19 more tables. He begins to haggle. “So, with nineteen tables… I should be able to get them for 9,000 shillings each, right?”

“Oh, no.” The carpenter replied. “I’m thinking 12,000 shillings for each table.”

“What?” Our Italian friend was shocked. “Why won’t you give me a discount?”

“Because it’s a lot of work and I don’t want to do it!”

Hearing these stories made me realize something, not just about Tanzania, but about much of Africa, too. Western nations send a lot of support to countries on “the dark continent” and you often hear capitalistic talk of harnessing the 1-billion-strong population. If we can just bring them up to a certain level, the thinking goes, their own economies will take over and they’ll lift themselves up out of poverty.

The problem (if you can even call it that), is that many Africans have no interest in bettering their condition. This doesn’t sit well with our image-and-comfort conscious, materialistic, rush-rush, credit card sensibilities, but that’s the way many of them choose to live. Renato told me that pole pole isn’t just an excuse that some people use shrug off work. He tapped his temple and said, “Eighty percent of people down here really are pole pole in the head!”

Is it a lack of education that’s responsible a poor work ethic? Is ambition something that is learned? Or is it the genuine “nature” in the nature vs. nurture argument that dictates a person’s (or a whole society’s) drive to better themselves? That is, in the tropics where you can literally live under a palm tree if you like, where the weather tomorrow is always like it is today, and where food doesn’t have to be gathered and stockpiled for the winter; is it really worth a person’s time to be anything other than pole pole?

There’s talk of Africa becoming the next China. A place where first world nations buy up natural resources and harness cheap labor by creating factories for their products on the same continent. I’m sure deals will be made to extract the oil, the diamonds, and the precious metals, but I’m not convinced we’ll ever see factories in Africa churning out iPhones and LCD screens. I just can’t imagine the average African would put up with the sweat-shop environment for long.

After three months, I began to wonder: Is the African way of life any less valid than our western one? Before this trip I might have answered “yes” to that question, but now the only thing I’m sure of is that I’m not sure of anything anymore.

You must be logged in to post a comment.