Podcast: Play in new window | Download (13.8MB)

When planning a vacation, I sometimes waffle between wanting to have a thorough, scheduled-to-the-day plan versus one built completely on freedom and spontaneity. I usually opt for the latter. For instance, when Oksana and I decided to spend a month in Costa Rica, the extent of our planning was to buy a guidebook and book round-trip tickets to San Jose. Everything, including the hotel we stayed in our first night, was found after we arrived.

When planning a vacation, I sometimes waffle between wanting to have a thorough, scheduled-to-the-day plan versus one built completely on freedom and spontaneity. I usually opt for the latter. For instance, when Oksana and I decided to spend a month in Costa Rica, the extent of our planning was to buy a guidebook and book round-trip tickets to San Jose. Everything, including the hotel we stayed in our first night, was found after we arrived.

The same attitude that worked so well for us there, gave us some problems in Hawaii. After the first three days, we spent too much of our vacation time fretting about where we would stay. While I was never particularly worried, Oksana let the stress build up whenever our internet searches and phone calls for the next hotel dragged on too long. I can’t argue that it would have been nice to know, before we ever stepped on the plane, where we would be staying each and every night.

On the other hand, one of the best things about vacations is the unexpected discoveries. While at the B&B in Maui, we met up with a couple who raved about an exciting snorkeling excursion on the Big Island. Had we been locked into hotel reservations, we might not have been able to take advantage of their suggestion to pay for a night dive to swim with manta rays. As it was, we were able to plan our Big Island stay around that tour.

As soon as we checked into our Kona hotel, I called the company they had suggested, Big Island Divers, to get the scoop. $70 per person gives you a 1-tank night “dive” with sightings of mantas almost guaranteed. I asked if it was worthwhile to go as a snorkeler, and the woman on the other end of the line proceeded to describe the underwater wonders we would see. Prices seemed non-negotiable, despite the fact that we wanted to use our own equipment and wouldn’t need a tank of air. Still, it sounded good enough to reserve a spot for Oksana and me on their boat for the following day.

When the time came, Oksana and I drove to the dive shop. We paid for our trip, got fitted with wetsuits, and waited around while the rest of the divers on our boat readied their own equipment. We drove to the harbor behind the boat trailer and, once all 20 or so of us were on board, cast off just before sunset.

Our boat was fast and it only took us 15-20 minutes to reach the dive spot. As we watched the sun dip down into the ocean, boats from other dive companies anchored near us and divers prepared the site to attract the manta rays. As twilight darkened into full night, our captain lectured us on the rules of the evening, what we were likely to see, and how we were to interact, both with the mantas and with one another. At one point, a wetsuit-clad videographer climbed up onto our boat and spoke to us about the opportunity to purchase a DVD or VHS tape the upcoming dive.

Before long, we were suiting up and getting in the water. Each of us, whether diver or snorkeler, was given a flashlight. We were also outfitted with colored lightsticks that identified us as a group. Our blue lights, we were told, would help our guides keep tabs on us, and also help the video editors tailor the DVD specifically to our boat.

Once in the water, we grouped up – divers 30ft down on the bottom, snorkelers on the surface – and swam the 100 yards to the site. Without the sunlight shining down into the water, there wasn’t much to see. Even with my flashlight, I could only pick out the occasional fish from the green, monochromatic background… until we saw the “campfires” in the distance, that is.

The campfires were milk crates, each filled with four bright lights, resting on the ocean floor. As we swam near, I could see that the divers, a couple dozen of them, were sitting around in a large circle on the bottom. Each was pointing their flashlight upward, contributing its beam to the campfire’s glow. Plankton came for the light and the mantas came for the plankton. Already, hundreds of fish were schooling above the lights, encircled by the divers’ rising bubbles. A moray eel slipped in and out of their teeming mass.

Oksana and I linked hands, drifted to the edge, and just as our captain said to do, pointed our lights toward the campfire. The water was warm, and there seemed to be little, if any, current pulling at us. The surface was a slightly choppy, but not enough to flood our snorkels. We drifted in place, being careful not to lower our fins – we had been warned that even a light touch against a manta’s skin could hurt them.

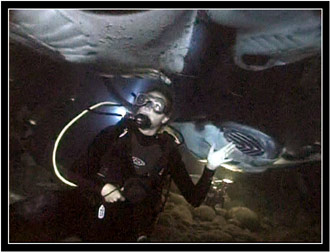

And the mantas materialized out of the dark. Already we could see five or six of them swimming over the divers and through the column of fish. They drifted in and out of the darkness, flapping their wings with a surreal, liquid fluidity that reminded me of aliens in some science fiction movie. We watched them from the surface as they undulated above the divers, mouths agape, catching and filtering the plankton.

Within minutes of arriving, a manta climbed toward us. It was at least 10 feet from wingtip to wingtip and its mouth was wide open. Unlike the first time I had seen a ray that size – in the Galapagos, where I didn’t know if might have been a more dangerous stingray – I wasn’t at all afraid. (Though members of the shark family, mantas only feed on plankton and have no poisonous stingers.)

It came closer; Oksana and I retracted our flashlights as we had been instructed. Apparently, mantas navigate mostly by sensing the electrical fields – non-conductive items such as rubberized flashlights and fins give off no such fields and are essentially invisible to them. Despite backing our lights all the way up to the surface, the manta still managed to run right into us. I laughed out loud into my snorkel from the sheer absurdity of it.

It was just a bump, really, and he didn’t appear to notice one bit. In fact, with a single strong flap of his fins, he completed his backwards arc and dove back down… just to loop back up towards us again. While I floated patiently on the surface, reflecting that the $70 price of admission had already made itself worthwhile, he continued doing loops right beneath us. After the first bump, though, he kept his distance. All of about 18 inches.

Oksana and I were thrilled, and if we had left right then, we would have gone home without a complaint. But it was then that the other snorkelers moved in.

Our captain, a fountain of information, warned us about the inconsiderate snorkelers. See, the divers had it easy. They all staked out their positions on the bottom and sat there, calmly observing the mantas. They were stationary and, consequently, there was zero chance that one diver would inadvertently bumble into another. No such luck on the surface.

As soon as the manta approached us, a horde of swimmers surrounded us, trying to get a better look. They were stupid; the snorkelers, I mean, not the mantas. If they had simply focused their flashlights together or aimed them at the campfires like Oksana and I had done, plankton would have collected in the water near them and the mantas would seek them out. Instead, they spent all their time and energy chasing the mantas around.

Which wouldn’t have been so bad if there hadn’t been so many snorkelers that night – there must have been 30 of us in the water. When I found myself surrounded, fins and elbows and knees bumping up against me and sometimes knocking off my mask, I became extremely pissed. Oksana and I, clinging to each other so that we wouldn’t lose each other in the mass of swimmers, would bear it as long as we could before trying to kick our way out of all those idiots jockeying for position. Because we weren’t supposed to dive or even lower our fins, it wasn’t easy.

That’s how the night progressed for us: Swim to the outer edge of the circle, attract a manta with our lights, happily observe it for a couple minutes, then swim away when the assh*les arrived. Frustrating as it was, the mantas more than made up for it.

Toward the end of our hour in the water, I noticed that the plankton was becoming so thick that I almost couldn’t see through their white reflection of my light. I started to swim away, to look for a better place, but Oksana rightly held me back. She realized with that much plankton in the area, we’d soon have quite a show. Besides, the waters were thinning out – early divers were running out of air and some of the snorkelers were hauling out onto their respective boats.

When we had first reached the campfire, there had been five or six mantas gliding in and out of the light. Only two remained when Oksana and I found ourselves among all that plankton, but they both converged on us at the same time. Directly beneath us, each began turning circles, back-to-back. It was like we were looking down at the junction between two gears, interlocked, turning in unison.

After that show, it was time to make the swim back to the boat. I noticed on the way there that we were the last group in the water and the mantas were being strung along by our lights. One-by-one we climbed up onto the deck and stripped off our wet suits while the mantas continued to loop near us, first in the beams our flashlights, then in the strong lights of the videographer, and finally beneath the deck lights of the boat itself. While the divers on our boat stowed their equipment, I had more than enough time to take out both my digital camera and camcorder to capture some above-water imagery.

Back at the dock, we were met by a woman who was taking the names of people who were interested in purchasing a DVD of the night’s dive. While Oksana tipped the crew, I spoke to her about our options. I was rather shocked to learn that the DVD would cost $70 – as much as the dive itself! The VHS was $45, but the Digital Media Specialist in me knew that the quality would suck. Still images could be purchased for only $20, but I learned that they were just screen caps from the DVD. I overheard someone say that there was a money-back guarantee, though, and asked her about that. Under her breath, but not really trying to hide anything, she said that if I didn’t like the DVD, they’d give us our money back. That convinced me. Wrote down my name and set an appointment, a day-and-a-half later, when we would come by to pick it up.

When we finally did stop by Big Island Divers to pay for our DVD, I mentioned the money-back guarantee. The person behind the counter made a comment that I found rather hard to believe: “I can’t imagine that you’ll use it – in the seven years we’ve been selling them, no one has ever asked for their money back.”

I didn’t say anything at the time, but I couldn’t quite believe that, at $70 a pop, not a single person had ever returned their DVD for a refund. The video couldn’t be that good. At any rate, I consoled myself with the thought that I had an easy, albeit immoral, way out of paying. Back at our hotel, I could easily copy the DVD files to my laptop’s hard drive. If I didn’t think it was worth $70, I could get my money back AND keep the video.

Oksana and I popped the DVD into our portable player and gave it a look-see. Turned out, it wasn’t that bad at all. There was only 20 minutes worth of video on the whole disc, but the footage had been edited down to just the people on our boat. The video was clean and the mantas and divers were all amazingly well-lit, especially considering the conditions under which they were shooting. Oksana and I even made an appearance – we’d thrown out some astute “thumbs-up” and “hang-ten” signs when the bright lights had been pointed our way.

$70 for a 20-minute DVD+R with stock music, stock credits, and a stick-on label. I guess the market will bear that price tag, but it still seems awfully high to me. The comment about the lack of refunds bugged me for days until I suddenly realized why nobody had ever taken advantage of their return policy (if indeed that statement was true): Most people wouldn’t have been able to watch the DVD until they returned home from their vacation; by then it would have been too much hassle to send the DVD back.

Oksana and I decided to keep the disc, though. If only so that we could show you this:

Wow that looks amazing. I have been to stingray city and this size of these guys are huge compared to the stingrays. Wow nice video too. Thanks …jenn

[…] At the risk of coming across as a complete Coulton fanboi (after all, I paired another song of his to one of my videos in a previous entry), I’ll trackback to his blog entry about the song, I used, “I Feel Fantastic.” He really does make good music. […]

[…] Travelogues (1, 2, 3), […]

[…] Tinker with a blog long enough and you’re bound to see your readership grow and change. I’ve had friends tell me funny stories about how they stumbled across my website. Juneau’s small, but big enough that I’ve been introduced to people that already knew something about me because of what I’d written here. I keep an eye on my referral logs, and every month I’m surprised by something. Google is by far my biggest referrer (likely because my logorrhea produces plenty of keyword matches), and its search strings are enlightening. Probably the biggest spike I’ve ever had was when Steve Irwin died and hundreds of people hit my post on the Manta Rays of Hawaii. I’ve even had a New York Times Bestselling author post a comment here (though, I admit, that’s a bit of a cheat.) […]

That does look amazing.

Nice video.

I read a lot of interesting articles here. Probably you spend a lot of time writing,

i know how to save you a lot of time, there is an online tool that creates readable, google friendly posts in minutes, just search in google – laranitas free content source